East End Suffragettes: the photographs of Norah Smyth

2 November-9 February 2019

Tues-Sat: 11.00-18.00 daily

Admission free

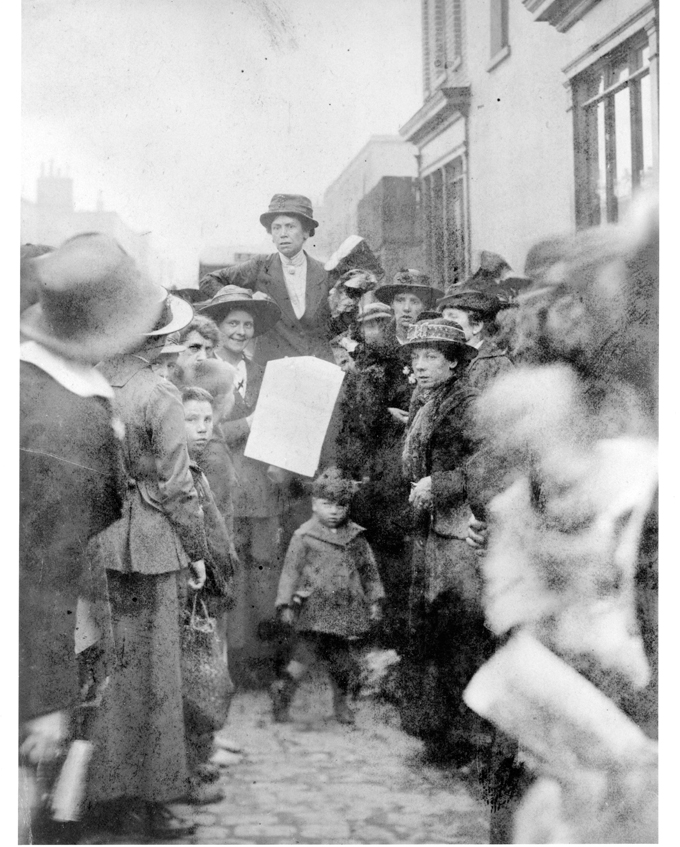

EAST End Suffragette photos from 100 years ago, are revealed, for the first time in Britain. The venue is the Four Corners Studio, 121 Roman Road, close to Bethnal Green tube station, East London. Exhibition opening is Tuesday to Saturday 11am to 6pm, until February 9. Pioneering campaign photos of the East London Federation of the Suffragettes (ELFS) from 1914 to 1916, are being shown. They have been loaned by the Institute of Social History in Amsterdam.

The photos are the work of Norah Smyth, used to illustrate workers’ conditions in the East End of London and the activities of the ELFS in its weekly paper.

Norah was originally inspired by the suffrage campaign of The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) led by Emmeline Pankhurst and daughter Chrystabel Pankhurst in 1911.

She soon met the other Pankhurst sister, Sylvia, and in 1912 they joined supporters and formed a branch of the WSPU in East London. They were moved by the terrible poverty of the working class in that area, and inspired by the history of trade union struggles such as the match girls’ strike in 1888 and the socialist ideas of the Independent Labour Party. They opened a shop in Bow Road, with a head board ‘Votes for Women’. Norah came from a wealthy family and used her inheritance to support the struggle.

During 1913, Sylvia was arrested and started hunger and thirst strikes until she was released to get better, ten times, under the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’. The branch was very active and supported strikes at local factories. Their orientation towards working class struggle was too much for the leaders of the WSPU, who focused on getting the vote for property owning middle class women.

By January 1914, Chrystabel demanded that the ELFS separate from the WSPU. This it did, becoming more socialist, adding the colour red to the traditional suffragette colours of white, green and purple.

The ELFS organised Women’s May Day parades from the East India Dock Gates to Victoria Park, six mile marches to Holloway prison to show solidarity with suffragette prisoners, and held open air meetings all over the East End from Canning Town to Hackney and Stepney. Every week they had a stall in Roman Road market.

Many men took part in the events and the police regularly used force against them.

For a short time in 1913 the ELFS set up a ‘Peoples Army’ modelled on James Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army and began drilling, to defend workers demonstrations and form protection for Sylvia against re-arrest. In March 1914, they set up a weekly paper called ‘The Womens Dreadnought’ as the ‘only suffrage paper in the country which makes a distinct appeal to working people’.

Articles covered workers housing and work conditions and struggles and their own campaigns. Here Norah Smyth’s photographs played a key role. In May, the ELFS opened their own HQ in 400 Old Ford Rd, which included two large halls, where meetings and clubs were held.

When World War 1 broke out in August 1914, Emmeline and Chrystabel Pankhurst immediately capitulated to the patriotic propaganda and dropped the suffrage campaign, whereas the ELFS became more resolute. They became pacifists and redoubled their support for working class families through welfare schemes in which local woman participated.

Unemployment rose as factories closed. Then conscription of the men left the women trying to care for the children on belated payments. Woman ended up working in munitions and clothing factories on sweated labour conditions. When the ELFS opened some food distribution centres (milk, eggs and barley) for starving woman and children, and communal canteens, hundreds turned up. They organised free nurseries and set up a shoe and toy factory to employ women.

The Dreadnought called for equal pay and working conditions, and rights for soldiers and sailors wives and ‘Down with sweating’. By 1915, when compulsory conscription was brought in, they campaigned against compulsion. State repression against these rallies increased.

One million working class soldiers were conscripted but many had no vote. The new Franchise Bill excluded poorer men, conscientious objectors, women under 30, and poor and widowed women from the vote. In March 1916, the ELFS changed its name to ‘ Workers Suffrage Federation” (WSF ) and demanded universal suffrage for everyone over the age of 21 years. This was not achieved until 10 years later.

The two revolutions in Russia in 1917 inspired the WSL tremendously and they became revolutionary socialists. The new workers’ soviets in Russia seemed to them to parallel their community organisations. The Women’s Dreadnoaught changed its name to ‘Workers’ Dreadnought’ and stood for ‘household soviets and international socialism’. In summer 1917, it campaigned for ‘a paralysis of military force’.

The WSF set up peace pickets outside parliament with slogans ‘War is murder,’ ‘Soldiers in the trenches long for peace’, and ‘Bring back our Brothers’, and ‘Stop this Capitalist’s War’. In 1918, the organisation became the ‘Workers’ Socialist Federation’ and affiliated to the Communist International. Norah and Sylvia attended conferences in Russia and Amsterdam and Sylvia attended the second congress of the Third International in 1920, where the setting up of a British communist Party was debated. There were differences with Lenin.

They supported the ‘Hands off Russia’ campaign, and lobbied the east end dockers not to load munitions for the imperialist armies being used against the Bolsheviks.

The WSF fought to build a communist-type organisation until 1924, when the Dreadnought was ended. The 100 photographs in this exhibition reveal a huge empathy and respect for working woman and their families in the East End of London and a determination to fight for the vote and socialism in conflict with the capitalist state. It is not to be missed. N.B. Most of the information in this article came from the exhibition notices and an accompanying booklet.